Permissions: On expanding the field of writing

There seems to be something in the air and a moment of opportunity at hand. In writing the arts and humanities, in literary enquiries into the self, the social and historic—these things captured under the broad umbrella of ‘nonfiction’—writers are challenging ideologically-bound conventions, and transforming the way we understand form and genre.

The past decade or more has seen the emergence of

The Realpoetik1

1. See Jessica Wilkinson and Ali Alizadeh, ‘“Realpoetik manifesto: a declaration in

progress”,’ Victorian Writer, 34, 2012. (Also published in Cordite Poetry Review).

2. See David Shields,

Reality Hunger: A Manifesto

, Knopf, New York, 2010.

3. See John D’Agata and David F Weiss, We Might as Well Call it the Lyric Essay: A

Special Issue of Seneca Review, Hobart and William Smith Colleges, 2014.

4. See for instance, Maggie Nelson's, Bluets, Wave Books, Seattle and New York,

2009. Also Brian Dillon’s, Essayism, Fitzcarraldo Editions, London, 2017.

5. See Nina Lykke, Writing academic texts differently: Intersectional feminist

methodologies and the playful art of writing, Routledge, 2014.

of ‘nonfiction poetry’, Shields’ encounters with ‘reality-based art’2, a great

revival of the epigrammatic (very Barthesian) fragmented, often book-length essay3,

and huge interest in the form ‘We Might As Well Call’ 4

the lyric essay. Writing approaches in the tradition of ‘essaying’ as a genre-fluid site for

attempting to know

have also flourished, and have either run into – if they haven’t sprung from – feminist work in

the academy which places the embodied, and located writing subject within the critical

encounter.5

Through exploration and play with combinations of the poetic and the critical, the personal, imaginative and the historic, writers are pushing into new territory. Heated debates around ethics, representation, empiricism and truth speak to the high stakes of these moves.

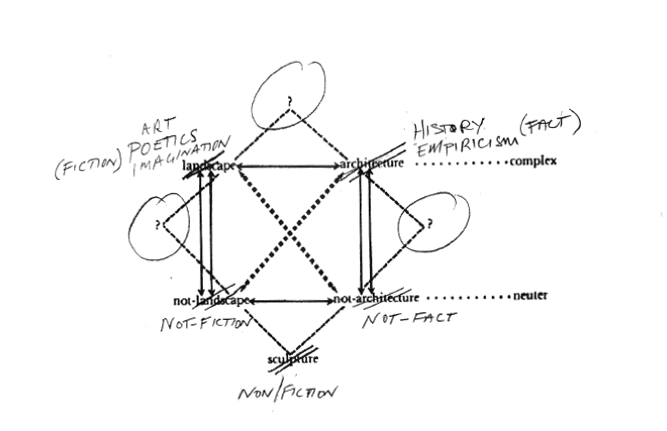

But what can Rosalind Krauss’s 1979 essay on sculpture bring to these twenty-first century concerns of writing?

One of the most important insights of Krauss’s essay Sculpture in the Expanded Field6 6. Rosalind Krauss, ‘Sculpture in the Expanded Field Sculpture in the Expanded Field’, October, 8 , 1979, p.31-44. was the ‘permission’ it opened ‘to think’ about sculptural form and practice in a completely different way. By bringing Krauss’s ideas to bear on the moves and forays of contemporary writers, we are able ‘to think’ past fixed forms and genres, and into an expanded field of variously structured, and multitude writing positions. These positions are radically fluid, but logically structured by the oppositional categories ‘criticism’ and ‘literature’ or ‘fiction’ and ‘fact’ – expressions of the classical opposition ‘poetry’ and ‘history’.

In writing about art, the expanded field accounts for the itching that writers clearly have to do more than simply explain, assess, historicise, and validate art in the service of various economies. It claims—reclaims—some intellectual ground in the encounter, and permits new literary/poetic/’creative’ ideas and techniques, throwing up new possibilities for writing and arts criticism.

Expanding the Field of Sculpture

By the late 1960s, Krauss7

7. Ibid., p. 30

observed that ‘rather surprising things’ had begun to be called sculpture. She noted: ‘narrow

corridors with TV monitors at the ends, large photographs documenting country hikes, mirrors

placed at strange angles in ordinary rooms and temporary lines cut into the floor of the

desert.’ Nothing, she wrote, with something close to exasperation, ‘could possibly give to such

a motley of effort the right to lay claim to whatever one might mean by the category of

sculpture. Unless that is, the category can be made to become almost infinitely malleable.’

Sculpture in the Expanded Field identified that in the late 1960s sculptural practice could no longer be understood through the lens of medium and material, according to the Art Historical lineage Krauss coined ‘the logic of the monument’. 8 8. Ibid., p. 33. Instead it was organising around enquiries into ‘the universe of terms that are felt to be in opposition in a cultural situation.’9 9. Ibid., p. 43. In the newly expanded field, the Art Historical category ‘sculpture’ could be seen as just one position within a field ‘in which there are other, differently structured possibilities’.10 10. Ibid., p. 38. This change to sculptural practice and the necessary adjustment to discourse it required, represented a ‘transformation of the cultural field’.11 11. Ibid., p. 41.

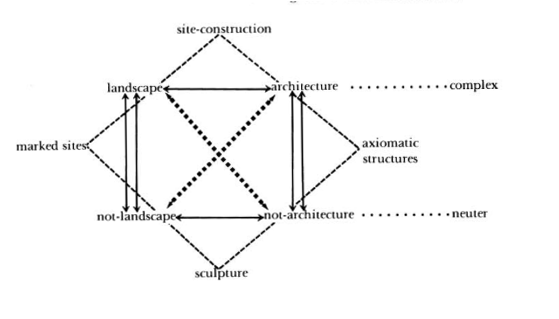

By drawing on a mathematical diagram called the Klein Group, Krauss proposed a structured and logically expanded field opening from the key opposition landscape/architecture. Through historical analysis, Krauss proposed that the logic of sculpture in Western art was inseparable from its role as a civic monument: ‘a commemorative representation’ sitting ‘in a particular place and speak[ing] in a symbolical tongue about the meaning or use of that place’.12 12. Ibid., p. 34-36. Citing the equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius in the Campidoglio in Rome as a particular example, Krauss then points to Rodin’s Gates of Hell and his statue of Balzac as examples of failed monuments, representing the move into sculpture’s modernist phase. Here it becomes ‘the monument as abstraction, the monument as pure marker or base, functionally placeless and largely self-referential.’ The works of Brancusi are noted as particular examples of modernist sculpture negating its monumental function, depicting its own autonomy by reaching downward to ‘absorb the pedestal into itself and away from actual place.’ Arriving in the 1950s however, this exploration had entered ‘black hole’ territory, beyond the abstraction of the monument and into ‘pure negativity’ as a form without substance of its own: ‘sculpture is what you bump into when you back up to see a painting’ Krauss quotes artist Barnett Newman.

By the late 60s, sculpture was doing something different. Appearing as reflexive and hybrid explorations of built structure (enquiries of architecture) or conversely, what was outside it (enquiries of landscape) Krauss proposed this work was, at the same time, both connected to the sculpture’s history as a monument, and also radically different. She mapped this work onto a diagram called the Klein Group (or Piaget square) that transformed the key binary landscape/architecture into a ‘quaternary field that both mirrors the original opposition and at the same time opens it’.13 13. Ibid., p. 38. The expanded field of sculpture looks like this:

This explanation of the expanded field of sculpture is necessarily brief and incomplete, but the point for our purposes here is the identification of an historic and discursive endpoint, recognisable in a cultural form being expressed in its negative condition.

Expanding ‘nonfiction’

Some writers have pointed out that the ‘hybrid’ and ‘blurry’ (the descriptor that comes up

maddeningly often) category ‘nonfiction’ is also an expression of literary form in its negative

condition. It is ‘a literary/artistic category built on a negation’,14

14. David Carlin and Francesca Rendle-short, ‘David Carlin and Francesca Rendle-Short

Nonfiction now: a (non)introduction’, Text Journal of Writing and Writing Programs,

vol. 18, 2013, pp. 1.

15. John D’Agata, ed., The Lost Origins of the Essay, Grey Wolf Press, Minnesota,

2009. p. 467

16. Shields, Reality Hunger: A Manifesto. p.131

a ‘conditional state of being, and a negation of genre’,15

or as Shields16

would have it ‘an entire dresser labeled

nonsox'

(all those smalls that don’t fit any drawer, you know?). Ever since the 1960s and the emergence

of ‘nonfiction’ novels such as Capote’s

In Cold Blood

and Mailer’s

Armies of The Night,and the literary-influenced reporting of The New Journalists,

‘nonfiction’ has sat awkwardly as a category that cannot be absorbed into stable definitions of

either literature (fiction) or journalism (fact).

Mas'ud Zavarzade’s 1976 critique of the post-war American nonfiction novel argued that the form

was a ‘narrative manifestation of the epistemological crisis’17

17. Mas’ud Zavarzadeh, The Mythopoeic Reality: The Postwar American Nonfiction Novel.

University of Ilinois Press, Urbana, 1976, p.41.

18. Ibid., p.vii.

in the late twentieth century. The ‘nonfiction’ narratives of the 1960s signified that the

‘antithetical narrative poles’ of the fictional and the factual were ‘no longer capable of

dealing with current literary realities’.18

In a similar way, Lehman’s 1997 analysis of ‘the contradiction of a nonfiction text’19

19. Daniel W. Lehman, Matters of Fact: Reading Nonfiction over the Edge, Ohio

State University Press, Columbus, 1997, p. 41.

refers to Aristotle’s classical opposition between poetry and history (that underlies the

concept of factual/fictional narrative poles), and also points out nonfiction’s unresolved, and

problematizing, suspension between it.

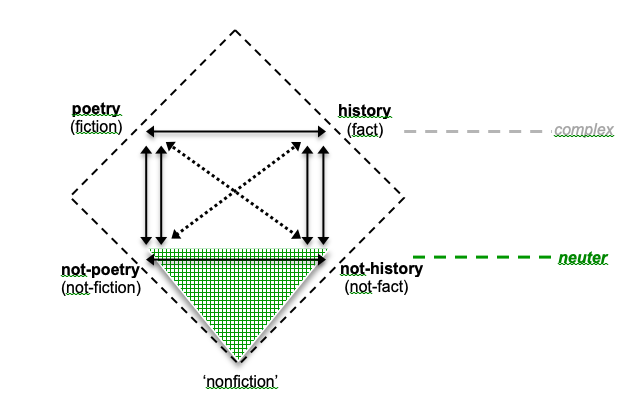

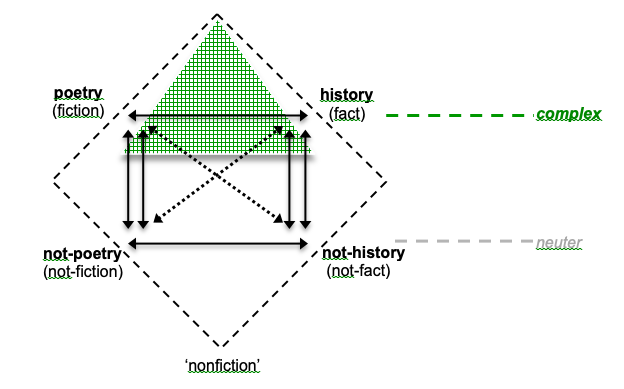

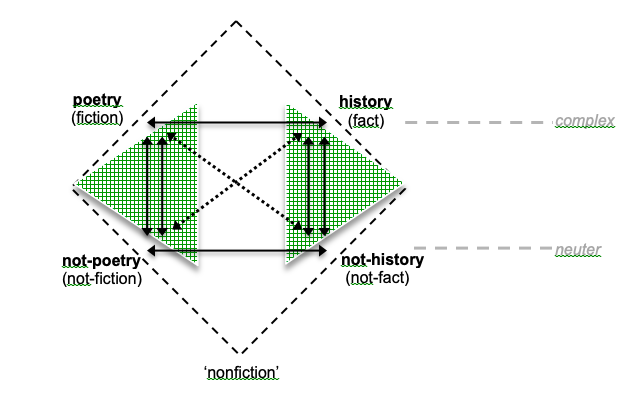

In the language of the expanded field, these critics are describing the ‘neuter’ condition of nonfiction. It is neither fiction, nor fact, but rather, ‘the combination of exclusions’20 20. Krauss, ‘Sculpture in the Expanded Field’.p. 36. of the negative condition of both: what-is-not-history (or not-fact) and what-is-not-poetry (not-fiction). As in the expanded field of sculpture, by bringing the logic of the Klein Group to this situation, a field structured by three different relations of opposition is opened out from the key binary:

The logic of the Klein Group proposes three different relationships of opposition to the key binary: firstly, a pure contradiction between the key terms; secondly, an involutionary opposition running vertically on the diagram between the key terms and their negative conditions; and thirdly, a relation of implication, running diagonally across the diagram (i.e. the double negative that becomes the positive).21 21. Ibid., p.37. These oppositions characterise the different areas of the field opening out from them, each one structurally related to the main opposition, but different in the nature of this relation.

The neuter is the negative aspect of the field: the ‘combination of exclusions’ of the negative condition of the main opposition as we have seen. Directly opposite this is the complex, the positive condition of the field that challenges the ideological structure of the key opposition by somehow being both. On either side are the schemas that are concerned with reflexive investigations into each key term, and its negative condition. By bringing this method of expansion to bear on the term ‘nonfiction’, we open up a field of new possibilities.

Possibilities

Key in the transformation of practice in the expanded field of sculpture was the possibility

for artists to move within it, occupying any number of positions. Krauss identified that

sculpture had become detached from the logic of the monument, and had become instead, radical

fluid in form and medium. The

position

of a particular work within the field could be seen to be the new logic of sculptural practice.

The notion of writing

positions

is similarly useful for understanding the fluidity of contemporary writing. Terms being used in

current writing discourse like ‘bending genre’,22

22. See Margot Singer and Nicole Walker, eds., Bending Genre : Essays on Creative

Nonfiction, Bloomsbury Academic, London & New York, 2013.

23. See Carl H Klaus and Ned Stuckey-French, Essayists on the Essay: Montaigne to our

Time, University of Iowa Press, Iowa, 2012.

24. Rachel Blau DuPlessis, ‘f-Words: An Essay on the Essay’, American Literature,

68, March 1996, p. 25.

and ‘essaying’23

(the verb form that emphasises action and intent over formal restrictions) gesture toward this.

In her Essay on the Essay24,

Duplessis hits on the notion of something multiple and spontaneously available, indeterminate

but known, that might characterise the notion of a writing

position:

‘When a situated practice of knowing made up by the untransparent situated subject explores (explodes) its material in unabashed textual untransparency, conglomerated genre, ambidextrous, switch-hitting style—as if figuring out on the ground, virtually in the time of writing—that’s it.’

Writing positions within the expanded field can be understood as multiple, structured within the field but also indeterminate until they appear. Even as we identify the expanded field and the relational characteristics of each part, we cannot exactly know what an individual writer will produce from each position. What we can do, however, is look to some of the movements in contemporary writing, and begin to map it onto an expanded field.

In their ‘unavoidable and necessary’ 2012 manifesto of nonfiction poetry The Realpoetik Jessica Wilkinson and Ali Alizadeh proclaim ‘the unquantifiable potential of poetic writing to convey a deeper experience of reality and “real life” accounts than may be possible through nonfiction prose’. The Realpoetik proposes the poetic play of line and space, pause and rhythm, imagery, metaphor and frisson, as tools for unsettling the ‘historical landscape of facts and accuracies’. It is ‘an expansive literary space’ the manifesto states, where poets might engage with ‘auto/biography, history, politics, economics, cultural analysis, science, the environment, and all other aspects of life in the real world.’25 25. Wilkinson and Alizadeh, ‘“Realpoetik manifesto: a declaration in progress”,’ 2012..

The Realpoetik describes a writing position that could be located in the complex. It suggests poetic play as a method to give access to feelings, ideas and expressions of ‘the real’ not available in dominant systems of language. Where prose confirms and reproduces the dominant order of knowing and understanding, the Realpoetik proclaims the ‘immense power of the semiotic undercurrent of poetic language’ as revealed by the feminist scholarship of writing to express gaps and questions, historical blind spots and affective experiences.26 26. Ibid,.

The lyric essay is a form that could also be located in the complex of the expanded field of writing. Like the Realpoetik, lyric essaying similarly eschews the closure of linear prose and narrative line in favor of an associative, ludic, method using ‘imagery or connotation, advancing by juxtaposition or sidewinding poetic logic’.27 27. D Tall and J D’Agata, ‘“New terrain: the lyric essay”’, Seneca Review, 27, 1997, p. 7. In his various works of, and about, the essay, John D’Agata often refers to classical examples to make the point that lyric style has long been used by essayists to consider the ‘complicated, multidimensional, unpredictable, very messy’ business of being and knowing. Discussing Plato’s Symposium as an example of the rich tradition of ‘woefully unverifiable’ nonfiction writing, D’Agata28 28. John D’Agata, We Might As Well Call It The Lyric Essay, 2014, p.8. points to how Symposium’s digressionary, poetic style, that holds a story, within a story, within an essay, recounting memories – speaks to its concern that ‘knowledge is layered… and we probably couldn’t agree on what it really is or how it’s ever made or the best way to frame it for someone else to appreciate.’

Writing positions in the complex, can allow for what intersectional criticism acknowledges as ‘multiplex epistemologies’29 29. Ann Phoenix and Pamela Pattynama, ‘Intersectionality’, European Journal of Women’s Studies, 13, 2006, p. 187. arising from subject positions crossed by multiple relations of power and affective forces at once. These include intersecting and competing situations of class, race, gender, sexuality and embodied ability, that impact subjective inclusion and exclusion in different ways. These intersections may bring layers of contradiction, or present blockages to written expression, and call for the use of varied mediums, or multi-lingual or multi-disciplinary or multi-cultural responses (to suggest a few basic scenarios). A writer may find a great deal of complex personal, political and affective material must be worked through before they can arrive anywhere near the privileged clearing in which conventional writing positions reside. A writer may find they can never get there, but rather, wish to explore imaginary scenarios in which their full subjectivity has a place in the critical encounter. Or, the first obstacle might be the page itself, calling for moves into performed or ‘dimensional’ writing.

Here, the ‘lived, embodied and affective experience’30 30. Anna Gibbs, ‘Writing as method: attunement, resonance, and rhythm’, in Affective methodologies: developing cultural research strategies for the study of affect, 2015, p. 224. of the writer engaged in the difficult work of sense-making and assuming one’s voice is necessarily the first critical object that must be unpacked. In doing this, the writer reveals the act of writing as material and part of the process of thinking and discovering and coming-to-know something; it is not a transparent container for ideas that are captured fully-formed somewhere else. In this way, the possibilities open to writers in the expanded field is not about trendy experimentalism or glib formal play, but permission to write from positions that are non-unitary, relational, and multiply aligned – something like what Rosi Braidotti31 31. Rosi Braidotti, The posthuman, Cambridge, UK ; Malden, MA, USA, 2013. P.144 describes as ‘posthuman’ subjectivity.

Writing away from dominant knowledge systems and disruption through the play of language are ideas that have been around for more than a century. In her essay On Roland Barthes, Sontag 32 32. Susan Sontag, ‘Writing Itself: On Roland Barthes’, A Roland Barthes Reader, Vintage Classics, London, 2000, p. xiv–xv. nominates him as ‘a particularly inventive practitioner’ of a modern stylistics of refusal that goes back to the anti-linear forms of narration invented by the German Romantics. In the modern period, this manifested in fiction in the ‘destruction of the story’ and ‘in nonfiction, the abandonment of linear argument.’ It can be proposed that the moves remodelling linear long forms in modern literature and criticism, may be positions within the expanded field located in the parts opening out from the oppositions running vertically between the key terms and their involutionary other: the not-history, and the not-poetry.

Indeed, some of the current movements in writing nonfiction have been critiqued as simply a reprisal of modernist ideas (as if they are exhausted?). A review of Reality Hunger in the Harvard Crimson entitled ‘Shields’ Modernist Manifesto Arrives A Few Decades Too Late’33 33. James K. McAuley, ‘Shields’ Modernist Manifesto Arrives a Few Decades Too Late’, The Harvard Crimson, April 20, 2010. Viewed August 4, 2018, link comments that ideas around truth, authenticity and the artificiality inherent in traditional narrative structures are those that ‘most students of literature will have encountered at some point or other in their career’. There may be two points to make here: one is that certain systems only seem to have become stronger through the forces of neo-liberal market capitalism in the twenty first century, and hence the need for reprisal and re-engagement with these ideas; and secondly that there are different inflections this time around.

There can be no doubt that we are at a cultural moment where strain on the key opposition fact/fiction is now stretched to breaking point. But in the twenty first century it is not quite so easy to assert as Barthes did, that ‘reality is nothing but a meaning’34 34. Roland Barthes, ‘Historical Discourse’, in Michael Lane, ed., Introduction to Structuralism (New York, 1970, p.144-45. in the face of actual climate catastrophe. Empiricism matters much more now: the globe is warming; Trump did not pull the largest crowd on record at his inauguration. This must be accounted for. Instead of collapsing the binary between poetry and history into a flat pluralism, maintaining the foundational binary in the expanded field confirms that the historical positions poetry/history; fiction/fact are necessary, and that readers and writers are, in various complex ways, implicated materially and historically outside the text in what might be thought of as bi- or multi-referential plane.35 35. Lehman, Matters of Fact: Reading Nonfiction over the Edge, Ohio State University Press, Columbus, 1997, p. 4.

The moves available to a writer within the expanded field do not, either, discount the history or the importance of the conventional critical position. This essay itself is taking this position of detached, discursive argumentation because when it is available to a writer, it is appropriate and useful, and often necessary, for scholarly contextualisation and analysis. As a writer who has had full access to higher education, who has been able to make the most of these systems and use them to research various writing positions, the conventional critical voice is one that I choose to use here (this kind of essay can also be massive nerdy fun for its rhetorical problem-solving). In the expanded field, the positions of historical precedence: the critic, the journalist, novelist, do not disappear but simply become, as Krauss put it, ‘one term on the periphery of a field in which there are other, differently structured possibilities.’36 36. Krauss, ‘Sculpture in the Expanded Field’ p. 38.

That what was once ideologically prohibited may now be seen, and accounted for in discourse is one of the key insights of Krauss’s famous essay. The field of possibilities opened by this method of expansion goes some way to offering a way through the vexed terrain we find ourselves in as writers, trying to simultaneously explore diverse ways of knowing, understanding and responding, while observing the need to maintain historical precedents. These challenges may be seen as indicative of a moment that is upon us, where we need to think of things in a new way.

The expanded field allows that writing about is not all a writer can do, or sometimes all they want to do.Even the greatest critics have felt the straight jacket of prose to be creatively stifling. In his contemplation of the possibilities afforded by the essay form, Brian Dillon37 37. Brian Dillon, Essayism, Fitzcarraldo Editions, London, 2017, p. 100. shares his astonishment at reading Susan Sontag’s diaries (published after her death) in which she diagnoses the ‘problem’ with her celebrated critical prose: ‘thinness…It is meager, sentence by sentence. Too architectural, too discursive’. In 1970 she confesses ‘I think I am ready to learn to write. Think with words, not with ideas’. What was she getting at here? In the expanded field of writing we may think with words and write from, with, and through ideas. There is movement and play as well as precision, and above all possibility.